Old Valve

AKA: single barrel, gas-powered plasma canon |

I've been working on a natural gas pipeline project in the desert that more-or-less follows Interstate 40 from Needles to Barstow (140 miles). The pipe is 30-inches in diameter with a wall thickness of 1/2-inch. The working pressure is about 900 psi, but it is greatly reduced while we work on it (to less than 1/2 psi at some times). From Barstow, the gas is ultimately delivered to southern California.

The pipeline was built in the 1950s, and the gas company needs to check the pipe for corrosion. To do so, they send instruments (called "pigs") down the inside of the pipe that take readings of the corrosion. There are a series of different pigs in a pigging operation, but the main "smart" pig uses strong magnets and powerful computers to measure the thickness of the steel pipe. By inference, where the pipe is thin, it is corroded. If there is too much corrosion, the gas company must dig up the corroded spot and repair the pipe. |

New Valve

(aka multi-barrel, gas-powered plasma canon) |

The current problem for the gas company is that the 30-inch pipe has valves every 10 miles that are only 24-inches in diameter. A 30-inch pig cannot pass through a 24-inch valve.

So the first matter of business was to replace the old valves with new and improved, 30-inch valves that the pig can fit through. |

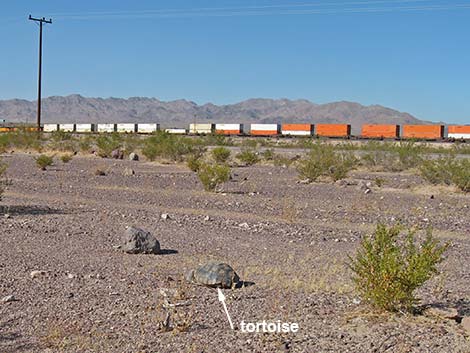

Tortoise along roadway |

I started in July, and it is now mid-October. My job on this project is to ensure the safety of desert tortoises, which are listed under the Endangered Species Act as "Threatened," one step below the worst category of "Endangered." Under government permit, the gas company is allowed to "take" (a legal term that more-or-less means kill) two tortoises per year in their entire southern California desert region on all of their many repair projects.

The gas company takes this very seriously, and unfortunately, they killed one back in May.

The main danger for tortoises on this project is being hit by vehicles, so one of my main job functions is to drive slowly ahead of construction vehicles looking carefully for tortoises. We need to spot hatchlings just as much as full-grown adults, so I constantly scan the roadway for 2-inch-long hatchling tortoises trying to disguise themselves as one small stone among many.

|

Tortoise in the desert |

We start our work by surveying the work areas and roadways to locate tortoises. We do this so we know where our "watch out extra carefully" areas are located. Much of the eastern and central portions of this pipeline run through great tortoise habitat, and we have found about 120 tortoises and sign (burrows, scat, tracks, etc.) of many more along that portion of the pipeline. |

Commuting to work (another biologist is leading the parade) |

Next, we escort the trucks and equipment to the worksites where they will dig up the pipe to expose the old pipe and valve.

There are 13 valves and two other features on this project, so we will have 15 "dig" sites, each of which is about 10 miles apart. |

|

Other than the clouds shading the scene, this is a typical worksite. The long, straight road follows the pipeline over the horizon, and every 10 miles or so we stop to work on a valve. |

|

As I say, we spend a lot of time escorting vehicles. Here, in my rear-view mirror, I am escorting a side-boom crane down the right-of-way. We escort trucks and equipment such as this because we have nothing to do but watch for tortoises, while they are doing everything they can to keep their rig on the road. We figure they don't have time to watch for little tortoises. |

Digging up old pipe |

Here a "digging crew" is working to expose the old pipe and valve.

A biologist is monitoring the construction activity to ensure that procedures are followed to protect tortoises and also to keep tortoises out of harm's way should one walk into the work area. This could involve the biologist calling a stop to all construction work until the tortoise moves out of the area on its own, or it could involve helping the tortoise exit the area quickly and safely. |

Exposed pipe and old valve |

Here a "digging crew" worked for three days to expose the old valve and pipe. It doesn't show well in the photo, but there is a metal screen fence around the pit to keep tortoises from falling in. There is also an orange plastic fence to keep humans from falling in. |

Tortoise fence and human fence |

After they dig the pit, the crews must install temporary fencing around the pit to ensure the safety of tortoises and of humans. For tortoises, the crews use wire-mesh fence that is 36 inches high. Crews bend the fencing at 14 inches, set it on the ground with the 22-inch segment upright, and cover the 14-inch segment with dirt to create a barrier that tortoises can't dig through.

Outside the tortoise fence, the crews erect orange plastic snow-fencing. This is to keep humans from inadvertently falling into the pit. They also set up highway barricades with reflectors and flashing lights to warn humans of the hazard within. |

Coating inspection instruments |

After the pipe is exposed, the first step is to inspect the old coating. Inspectors look for cracks in the coating and places where the coating separated from the pipe. They will use this information later when examining the old pipe for corrosion, and hopefully will better understand the relationship between problems in the coating and problems in the pipe. |

Coating removal |

After the old coating is inspected, it is removed. The coating is coal tar over a felt liner. In the 1950s, they used a felt liner that had a small amount of asbestos in it, so the coating is considered hazardous material. Men in full coveralls and gas masks remove and package the coating, then ship it off for proper disposal. These men seem to be the hardest working people on the project. |

Coating removal |

During coating removal, biologists monitor the activity, but we stay clear of the work area and hopefully stay upwind! |

|

Cutting out the old valve assembly. During valve replacement, the gas company reduces the pressure inside the pipe to less than 1 psi. By keeping some pressure inside the pipe, and by working hard to let as little as possible escape, they keep air out of the pipe. With no air (oxygen) inside the pipe, there can be no fire inside the pipe, and therefore no explosion.

Have you ever wondered why there are always so many people sitting around doing nothing on construction sites? Read the next segments for one answer. |

|

Lifting the old valve assembly out of the pit. Note that the end of the old is covered with wet burlap. This keeps air out of the pipe while the valve is being replaced.

We had one exciting moment when something went wrong and a large (at least it seemed large to me) fire ball erupted into the sky. The six men in the pit scrambled to safety, and the four men on "fire watch" quickly extinguished the flames.

One heroic guy went back into the pit to cover the pipe and contain the gas, and while there, kept calling for a fire extinguisher. The guys on fire watch kept spraying him with their dry-power fire extinguishers until they realized he wanted a fire extinguisher, not be be extinguished himself. The guy was heroic, but a bit of an ass, so I could only chuckle about his situation when it was over. |

|

Lifting the new valve assembly into place. Everyone gets out of the pit and out of the way when a 23,000-pound pipe is in the air. |

|

Welding the new pipe in place. It doesn't show, but there is always some pressurized gas inside the pipe, so the gas burns outside the pipe while the welders are working.

Note the guy in the background sitting around "doing nothing." He is on "fire watch," and his job is to say alert in case of fire. The pin on his extinguisher has already been pulled, and he is prohibited from eating, talking, or doing anything that could distract him from the business of being ready to put out a fire. There are always four or five men on fire watch during welding operations. |

|

When the new valve is being set in place, the welding crews place 4-inch by 5-inch, 4-ft long wooden timbers (cribbing) under the pipe to hold it in place. Cribbing makes a good place for things to hide when they get into the pits. We always look carefully around the cribbing for tortoises before crews enter the pit, but what I think we are really looking for rattlesnakes and scorpions. The crews often think we just get in their way, but they always like us to go down in the pit first to clear out the rattlesnakes. So far, I haven't found any, but I have found deer mice, pocket mice, and a few lizards. |

|

Before the pipe can be reburied, the cribbing must be removed, so another crew builds concrete supports under the pipe to hold it in place during the back-filling process. |

|

A new concrete support under the pipe. "V-8" means this is Valve 8, which is half-way along the pipeline. |

|

Before the pipe is buried again, it is coated with special epoxy paints. Here the crew works while a tortoise looks on, proving that our efforts help, but the tortoise fence is a real lifesaver. |

|

When everything is finished, the crew "back fills" the pit. |

|

Here, a back-fill foreman watches as a front-end loader brings dirt from the spoils pile to the pit and dumps it in, and a backhoe with a sheep's-foot tool compacts the dirt around the finished pipe and new valve. |

|

Hauling away an old valve assembly. We do a lot of escort duty... |

|

Graveyard of old valves at a gas company facility. These pipes will eventually be shipped off and engineers will examine them carefully to learn more about the corrosion process. Eventually, the metal will be scrapped for recycling. |

|

Sunset at one of my many offices. This is the best part of this job for me -- living in the desert. When I started in July, the days were in the 115-degrees range, and I got used to living out in that kind of heat with no ice or air conditioning. Now on October, the days and nights are getting cold -- and I am getting used to this too! In fact, now 93-degree days feel really hot and nights in the 50s with a breeze seem really cold. |

|

At the end of the day, this is what we want to see: a tortoise with a happy face! |